In recent years, efforts to increase awareness and understanding of the culture of the Ainu (the indigenous people of Hokkaido) have been reinvigorated. Sekine Kenji, a local teacher of Ainu language, discusses the interesting facets of the language, and recommends places where travelers can see artifacts and learn more about the Ainu way of life.

(Featured image: Courtesy of The Foundation for Ainu Culture)

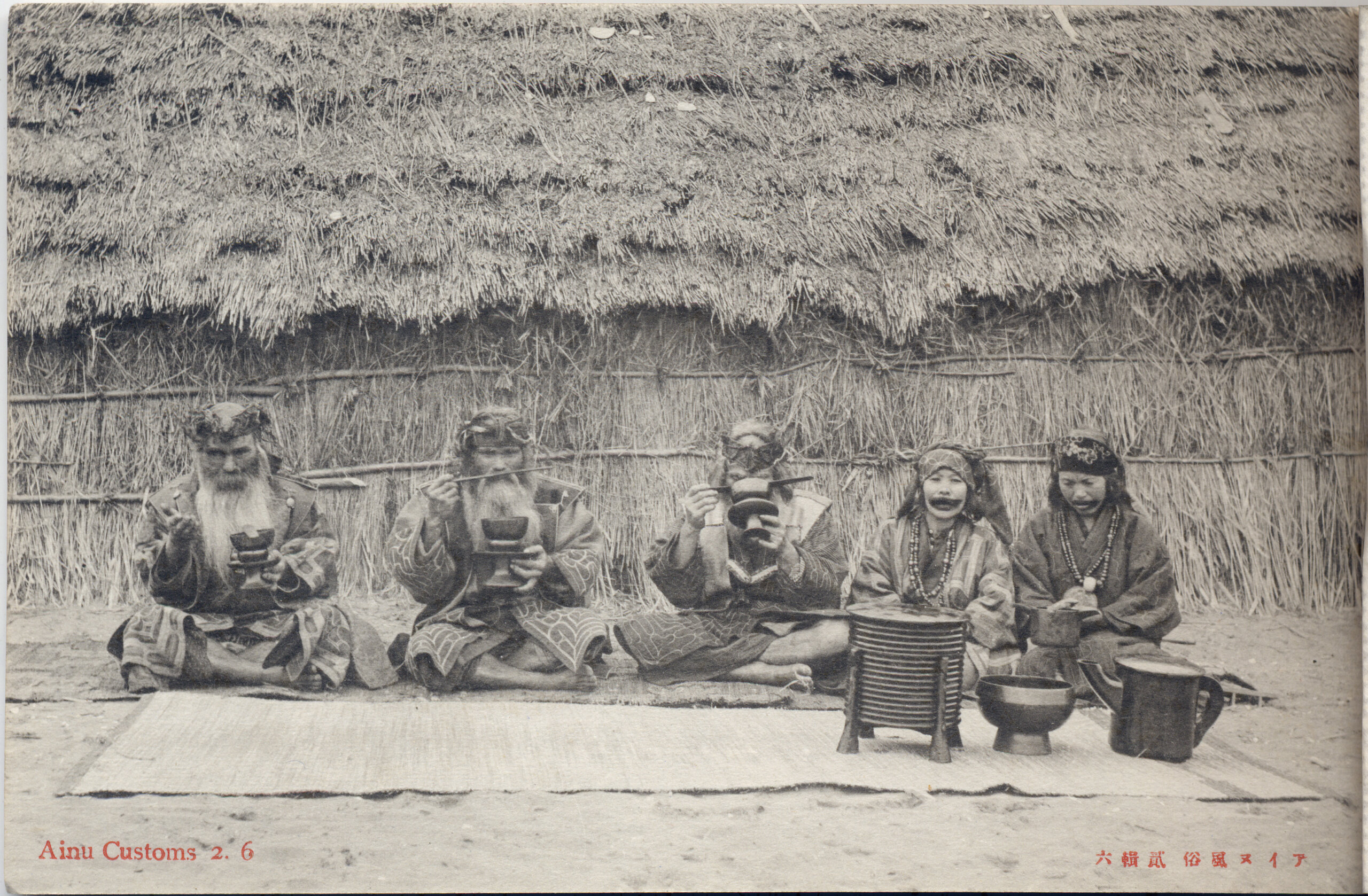

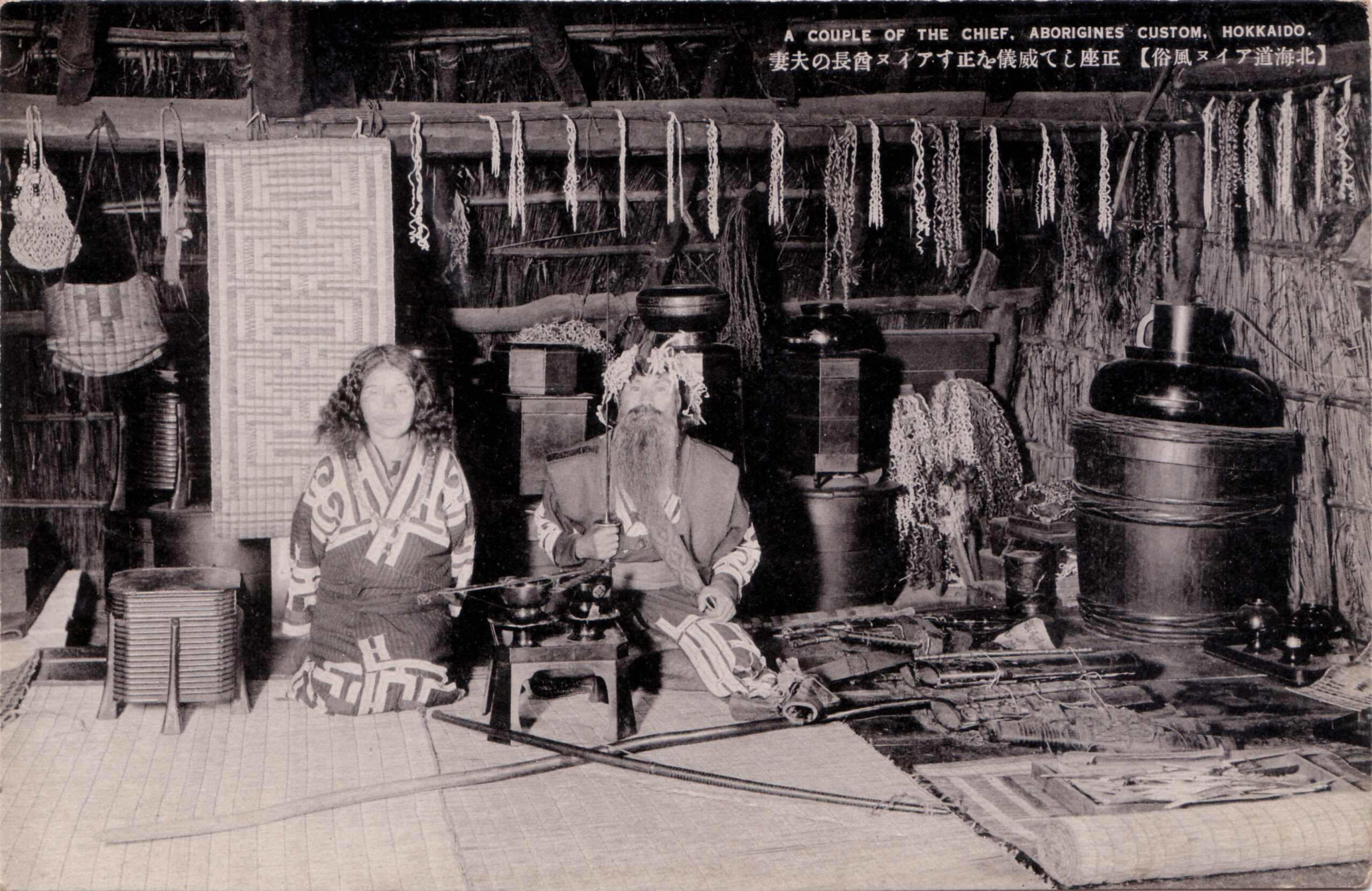

The history of the Ainu—the indigenous people of Hokkaido—dates back thousands of years, with some estimates suggesting that their roots lie with migrants arriving from the north about 30,000 years ago. During the Meiji Restoration of the late 19th century, Hokkaido was annexed by Japan, and policies were put in place to enforce the assimilation of Ainu people with those from the mainland. As a result, Ainu culture faced extinction. However, despite centuries of repression, there is a substantial number of people who identify as Ainu still living in Japan today. Sekine Kenji, born on the mainland of Japan and now a teacher of Ainu language in Nibutani, Biratori-cho, Hokkaido, explains that in recent years, Ainu culture has been gathering more attention. As Sekine suggests, “Efforts to preserve all aspects of the culture, from its artifacts and art forms to its language, have made experiencing Ainu culture easy for locals and tourists alike.” A notable example of the boom in Ainu appreciation is the manga series Golden Kamuy, first published in 2014, and the anime series of the same name that followed in 2018. Set in the early 20th century, it follows the adventures of a Japanese soldier working together with a young Ainu girl to find lost Ainu gold. With so many mediums to choose from, learning more about the indigenous people of Hokkaido has never been easier and can truly enhance your understanding of the rich history of the island.

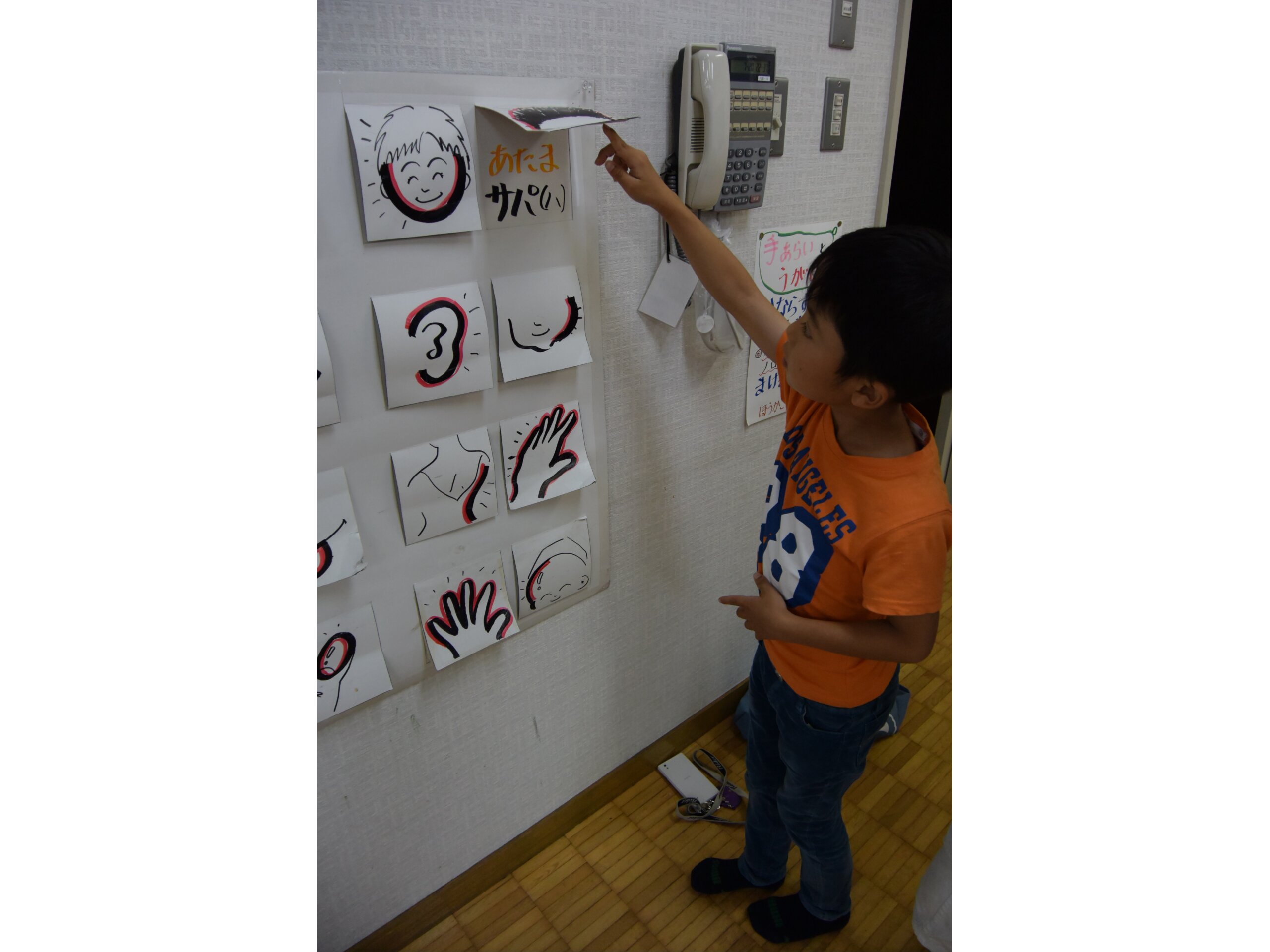

Like most cultures, Ainu is centered on the worship of gods—“kamuy” in the Ainu language, Sekine explains. “In the Ainu belief system, however, almost everything can be a kamuy.” Everything has a soul; all animals and plants are kamuy, as is the sun, the wind, and the rain. Perhaps it is due to this respect for all elements of the environment that there is such a wealth of historical objects remaining from the now-lost Ainu way of life. Unfortunately, after the Meiji Restoration, the freedom to use Ainu language in everyday life was no longer guaranteed, and as a consequence, parents stopped passing the language on to their children. However, some Ainu people of previous generations did their best to preserve the language by recording it in katakana or romaji (Japanese and English characters). Furthermore, due to the efforts of dedicated individuals today, such as Sekine, more and more people are learning the Ainu language. An interesting characteristic, Sekine tells us, is that “the distinction between voiced and unvoiced plosives found in languages like English and Japanese, such as between ‘k’ and ‘g’ and between ‘b’ and ‘p, is absent in Ainu.” Intriguingly, although separated by oceans, there are many similarities between the patterns and sounds found in Ainu and those found in Maori, the language of the indigenous people of New Zealand. Learning about the similarities and differences between your own language and that of an indigenous people can make for an enriching addition to a trip around Hokkaido.

Working as an Ainu-language teacher, and specifically for children, Sekine is at the forefront of efforts to preserve Ainu culture. Carrying out cultural exchanges on behalf of Japan with other countries eager to preserve their own indigenous heritage, such as New Zealand, Sekine also regularly holds Ainu-language classes for a wide variety of students in Nibutani. He explains that while some might see Ainu as an endangered language, it is very much alive, and in some cases exists right under our noses—with place names such as “Sapporo” in fact originating from Ainu. Sekine also offers an insight into the meanings behind certain Ainu rituals. In Ainu culture, he explains, “it is believed that kamuy come to the world of the humans in order to return to the kingdom of the gods with souvenirs, and when Ainu hunt animals or gather plants for food, they always thank the soul of the kamuy for nourishing them before sending it back on its way.” For such ceremonies, one item that is of particular importance is the inaw, a piece of wood carved into a twirl shape that is highly desired by kamuy, as it is believed to turn into gold or silver when taken back to the kingdom of the gods. Inaw can be seen at museums throughout the prefecture, and keen-eyed travelers might even be lucky enough to spot them dotted around outdoor settings.

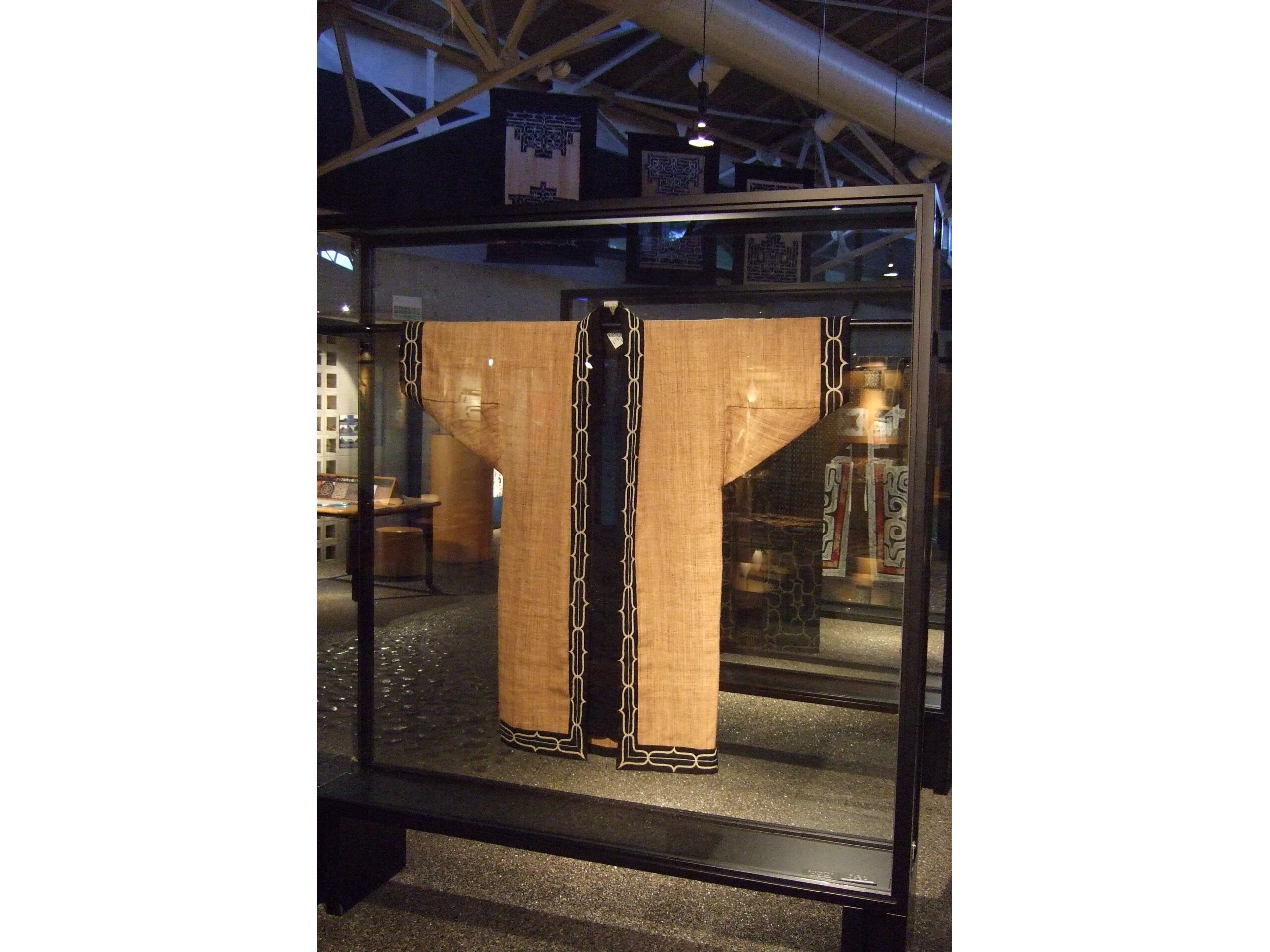

For visitors wishing to see artifacts from Ainu culture firsthand, the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum has over 1000 exhibits from all areas of daily life on display, with clothing thread made from wood fibers being one exceptional highlight. Moreover, at the newly opened Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park in Shiraoi, in addition to replicas of chise (traditional Ainu buildings) and an extensive collection of artifacts, an especial charm is the many Ainu employees who showcase traditional music and dancing. Make your trip to Hokkaido that touch more magical by taking the time to learn about this unique, ancient culture, which very much still lives on today.

Sekine Kenji

Born in 1971 in Hyogo Prefecture. In his twenties, visited Nibutani in Biratori Town as part of a trip around the whole of Japan, and decided to relocate there permanently. Began learning the Ainu language from around 2005, and later became a teacher of the language himself. Former assistant curator of the Nibutani Ainu Cultural Museum. Currently works at the Biratori Town Board of Education, as well as teaching classes at local elementary and junior high schools as an Ainu-language teacher.